The Healing Humanism of Amenra

Stunning concerts sold out in a flash and a recognizable visual concept propagated by a worldwide network of dedicated fans: Amenra have managed to pull it off for over twenty years, on its own steam and without concessions. A portrait of a West Flemish metal band that far exceeds the genre and puts bandages on gaping wounds.

Your life changes when a loved one passes. Colin H. Van Eeckhout, front man and driving force behind Amenra knows all about it. He lost his father when he was twenty and channeled the helplessness and anger that ensued into music – first in the West Flemish hardcore scene, and since 1999 in Amenra. To this day he still shrieks and sings the existential pains from his body. Behind him: four kindred spirits, rough diamonds whose piercing guitars and pounding drums lay down a wall of sound.

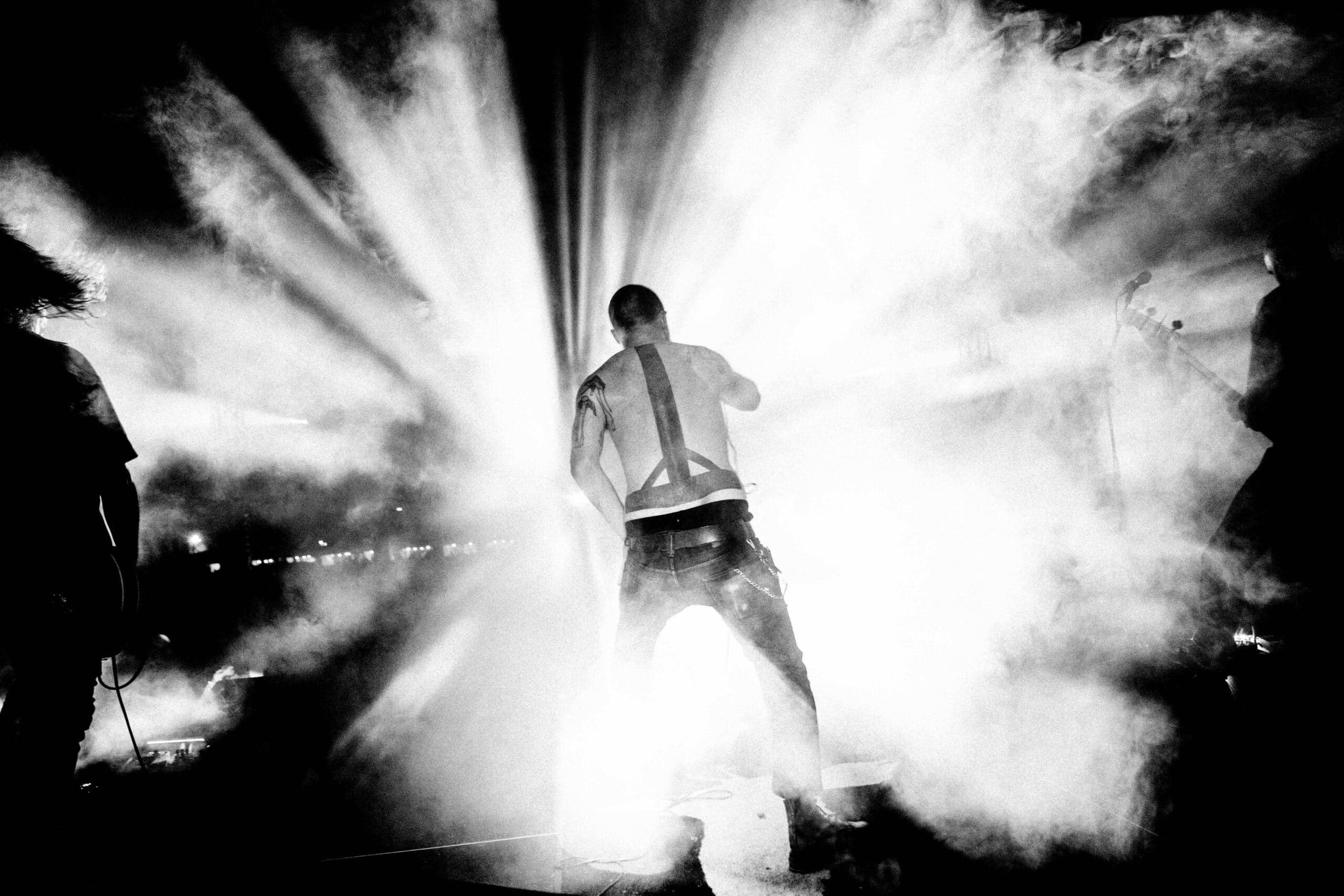

Amenra

Amenra© Stefaan Temmerman

Live, Amenra’s music is merely part of an overwhelming total experience full of contradictions: earsplitting passages and equally impressive silences, light and shadow, dramatics and modesty, torture and absolution. The result is a cross between concert and performance. Van Eeckhout is at the centre of it, with his arched back always turned to the audience, microphone in one hand and the other clawing at some invisible enemy or desperately grasping at a straw to hold onto. It all looks like an act, but it is much more than that. It is the human condition, summarized in a sensually arousing spectacle of sound and images.

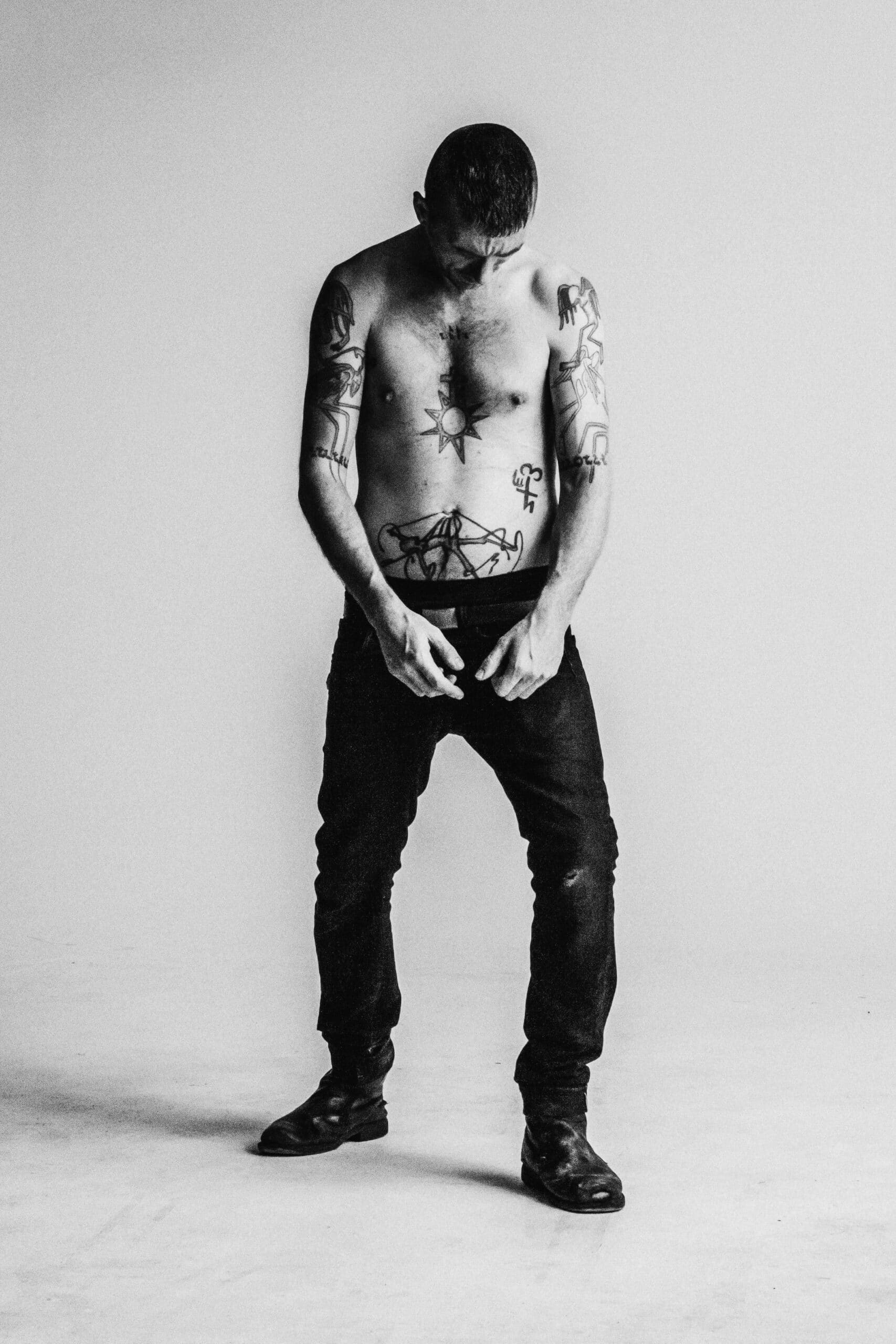

Colin H. Van Eeckhout shrieks and sings the existential pains from his body.

Colin H. Van Eeckhout shrieks and sings the existential pains from his body.© Stefaan Temmerman

On stage, the band are only silhouettes against a backdrop on which black and white films and visuals are projected. Their songs constantly moving from hard to soft elicit quite a few contradictory emotions: sadness, fear and frenzy, but also hope and the doggedness to deal with torments. It is lashing out and anointing at the same time. Amenra poses a universal question: how to deal with pain, suffering and emotions that are too severe to deal with alone?

Amicitia fortior appears to be the answer. Stronger through friendship. Comradery and solidarity as balsam for the soul. Van Eeckhout, whose father was a Free Mason, noticed that Latin motto on the masonic temple in Kortrijk, and made it the band’s slogan resolving to celebrate the principle that lay behind it in everything that would animate Amenra in future.

Anyone attending an Amenra concert, does not go just to experience the primal force of their music, but also to be part of a fellowship where pain is the greatest common denominator of all its members. Anyone suffering from grief, no matter how seemingly small or unimportant, finds catharsis in the audiovisual rituals Amenra puts on stage, as well as in the knowledge that the spectator next to him also suffers from the miseries that are a part of life.

The ‘tripod’ of Amenra, a kind of trampled on crow – a collage of three crow’s legs.

The ‘tripod’ of Amenra, a kind of trampled on crow – a collage of three crow’s legs.Right from the outset Amenra reinforces that solidarity with sinister, attractive but also very recognizable visual concepts that are also extended beyond the confines of the stage. On their album’s artwork, on the T-shirts (that do not even have the band’s name on them) and tour posters, displaying dead birds, whether nailed to a crucifix or not, church portals and ghastly hell hounds. And then there is the ‘tripod’ a kind of trampled on crow – a collage of three crow’s legs – that many fans have had immortalized on their bodies as a badge of honor. Devotees of Amenra and everything the band represents recognize each other without having to exchange a single word, like members of a secret society operating in public.

The common theme running through everything Amenra does is religious symbolism. Each one of their albums is considered a mass (from Mass I to Mass VI) songs with titles such as Offerande (Offering), Ritual, Am Kreuz. Nemelendelle (West Flemish dialect for ‘heaven and hell’) and Diaken (Deacon) refer to faith and rituals and their videoclips are beautifully photographed, hypnotic works of art pervaded with heathen symbolism and mysticism. Performances often take place in desecrated churches and Christian graveyards.

Colin H. Van Eeckhout

Colin H. Van Eeckhout© Stefaan Temmerman

The body of front man Colin H. Van Eeckhout is already something of a mystical object in and of itself. On his back, the body part most visible during concerts, is an upside-down pair of gallows in which Old Germanic, Norse and mystic symbols are fused together: the death rune, Thor’s hammer, and the cross of St. Anthony. On his arms and legs demons and angels seemed to be locked in the throes of combat. Spread across his body are characters from the Theban alphabet, the language of witches. His body is a canvass telling the story of his life, of his daily struggle against existence.

Sometimes that body must also give up something. Accordingly, Van Eeckhout had his nipples removed. They are useless to a man, in his opinion. He had a female artist ornament them with silver and will later leave them to his children. ‘Sucking it up for a good cause,’ is how he described the pain and suffering it entailed in an interview with Belgian newspaper De Morgen. On stage too Van Eeckhout often seeks out the extreme. In 2017, during the presentation of Amenra’s most recent album Mass VI, he had himself pierced with hooks from which heavy rocks were fastened. Years before that he had already had himself hoisted by his skin, with his arms spread like Christ.

Mass VI, the most recent album of Amenra

Mass VI, the most recent album of AmenraStill neither Van Eeckhout nor the other members of Amenra suffer from a messiah complex. They cherish the appreciation for their art but shudder at idolatry. After each performance the singer is the first to show up behind the merchandise stand, where he engages in conversations with fans about the struggles inherent to life. The others join him as soon as the instruments are loaded in the tour bus. They still adhere to the do it yourself ethos.

That is something that also marks them out from many of their colleagues: even though they have gigs from New York to Tokyo these days and easily draw an audience of 10,000, they still take matters into their own hands. They do not have a manager and are in large part responsible for their own promotion. Van Eeckhout, the only one of the five band members engaged fulltime in its activities, maintains contacts with fans through social media. Amenra also always takes along its ‘sixth band member’ when on tour: a regular sound engineer who makes sure that band always sounds and looks good. They consider what they are doing too important to entrust to people who do not know the group and its sensitive needs.

So Amenra does not have to make any concessions. They have ensured their own independence by expanding the Church of Ra in a wholly organic manner over the years, into a creative network of bands, graphic designers and artists who follow on from Amenra’s philosophy and approach and boost one other to greater heights. Groups like Oathbreaker and Wiegedood (Cot Death) who started out in Amenra’s shadow have now made international names of their own. Amenra was also a springboard for Stefaan Temmerman, still the group’s regular photographer. There are plenty of others who, with the right attitude, have benefited from Amenra’s success and vice versa.

‘I hope that we are able to communicate with people with what we make and point out the limited character of a human lifetime,’ Van Eeckhout was put on record as saying in De Morgen. ‘To show them what pain means and how to overcome it. To tap into the good in people.’ Even though Amenra may rave about religion, the core of their message is out and out humanistic.